The decision in EIS v LELO Oceania[1] underscores the importance of clear definitions, reproducible testing parameters, and credible experimental support in the context of FemTech inventions – particularly where biological interfaces are involved.

What the case was about

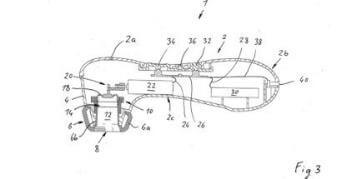

The case centred on a patent for a handheld “pressure-wave massager”, a device that uses rhythmic pulses of air to create gentle suction and pressure sensations for intimate wellness. As shown in Figure 3 of the patent specification, the device featured a single-chamber cavity sealed by a flexible membrane that expands and contracts to generate the pressure waves.

Figure 3 from the patent specification, illustrating the pressure-wave cavity and flexible membrane central to the disputed claims.

The patent’s defining feature was the volume change ratio (VCR), describing how much the internal air cavity expands and contracts as it operates. This parameter was said to define the intensity of the air pulses when used on the clitoris but ultimately became the patent’s downfall.

The Court’s findings

Justice Downes found that the patent didn’t teach how to measure the VCR in real-world use. It failed to specify where the membrane starts, how the presence of anatomy affects pressure, or how testing should reflect practical use (including underwater). Without clear parameters or supporting data, the claimed “pressure-wave sensation” couldn’t be reproduced consistently.

The Court held that the patent lacked clarity, sufficiency and support under section 40 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) and revoked it. Although the invention was novel and inventive, those findings couldn’t save a patent that didn’t enable others to build a working device.

Why this case matters for FemTech founders

For emerging companies, the message is simple: technical creativity must be matched by technical clarity. FemTech products often bridge biology and engineering – and courts will scrutinise how parameters are defined, tested, and supported by evidence.

Three practical lessons stand out:

- Define measurable features precisely. Explain how metrics such as pressure, flow, or biological response are determined in real use.

- Support claims with credible data. Show a clear link between the claimed ranges and the supporting experiments.

- Account for user variability. Products that interact with anatomy must be reproducible across users and conditions.

Looking ahead

This case marks a turning point in how courts view sexual-wellness technologies – not as curiosities, but as legitimate innovations demanding rigorous science. For founders, it’s a reminder that strong FemTech IP starts not only with invention, but with evidence.

[1] EIS GmbH v LELO Oceania Pty Ltd (Liability Trial) [2025] FCA 1111