Since 2015, copyright holders have been able to seek injunctions against Internet Service Providers requiring them to block their customers from accessing sites which contain infringing content by way of Section 115A of Australia’s Copyright Act 1968. These provisions, equivalents of which exist in a number of other jurisdictions, have been colloquially known as “whack-a-mole” provisions – largely due to the ability for sites to pop back up again elsewhere after being shut down.

Over the last two years, there was some concern as to how effective Section 115A might actually be in practice for copyright holders. Playing “whack-a-mole” with online sites has the potential to be a full time and costly exercise and ease of use of the provision is paramount.

A review of Section 115A late last year, by way of the Copyright Amendment (Online Infringement) Bill 2018, saw changes that attempted to broaden the scope of the provisions. There were a number of changes, but a major change was to lower the bar from a ‘primary purpose’ test for an injunction to a ‘primary purpose or primary effect’ test. Under the new provision a copyright holder now only needs to show the Court that the relevant online location infringes, or facilitates infringement, of copyright and has the primary purpose or primary effect of infringing or facilitating an infringement, of copyright.

The first Court judgment to address these new provisions has recently issued in Australasian Performing Right Association Ltd v Telstra Corporation Limited [2019] FCA 751 (3 April 2019).

The case related to a number of websites where a user can “rip” streaming content (typically from YouTube) into an audio format – for example, a music video or FLV file to an audio MP3 file. An excellent and amusing summary of music videos is provided by Perram J at [1] to [6] of the judgment.

Perram J, provides the following comment on the revised s 115A and the “primary purpose or primary effect” test:

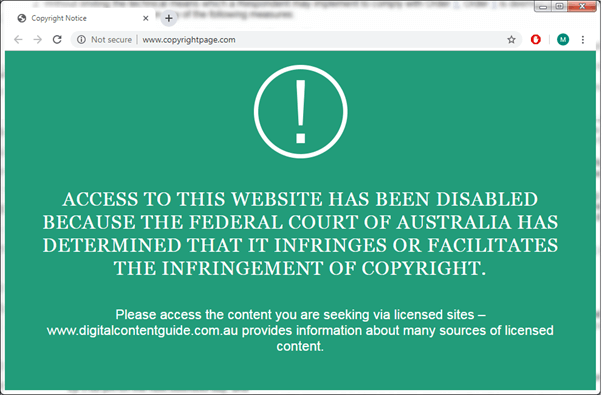

In granting the injunction against the online locations (websites), Perram J noted that the websites that were subject to the injunction were involved in industrial scale copyright infringement. Therefore, he did not need to consider the Applicants extensive evidence (which related to the websites being the subject of orders blocking access in other jurisdictions, and that the injunctions would be proportionate and in the public interest).